What's the longest journey you've ever taken through university bureaucracy? Mine is probably longer. After five months of appeals, I'm finally able to register at Concordia as a McGill student for an equivalent course. Just like the comic above - I was arbitrarily denied for no good reason after getting approval from six McGill and Concordia administrators. So like before, I employed a tactic to coerce this "outpost bureaucracy" which paid off! More on outpost bureaucracies later. Finally, while this is a story of eventual success, buckle down because I feel the comic above is no exaggeration.

I hope that by telling this embarrassing story university administrators will clear up some of their ludicrous and profoundly convoluted processes. I don't mean to unfairly target school administrators. But lets never forget that some of them are responsible for not fixing this mess. We need to complain more.

The Call to Adventure

In January 2015 I realized that if I schedule my classes right, I might be able to graduate as early as December 2015. Sweet! Lets make that happen! But I needed a diversity themed education course. Unfortunately, the only course overlapped by just 20 minutes and on only one day, with a computer science course I also absolutely needed.Lets talk to the diversity professor, Donna-Lee Smith. Maybe she'll be understanding?

I spoke to Donna after class. I appealed alongside another student who commiserated with me because she too was experiencing how the education department and science department refused to cooperate with each other. Both me her promised to prioritize attendance in Donna's class. We could make this promise because lectures in science courses are typically optional, or recorded, or just terrible. We just needed some flexibility in case there was a test and we needed to arrive 20 minutes late maybe once a month.

Donna's answer? No. Absolutely no. 100% attendance every single day is non-negotiable. Donna seemed like a good professor from her first class, but this was inexcusably inflexible.

She clearly did not care about our schedules or our lives. If I had a test or exam conflict, she was going to be a problem, not a solution. Donna is not the final gatekeeper in my comic, by the way. We've hardly even gotten started.

Refusal of the Call

So I dropped the course. Next I asked advisers for an exemption or if I could substitute a course. I was denied.One problem with pursuing a multi-disciplinary program is that no department feels you belong to them. I'm completing an arts degree (arts department) in computer science (science department) and education (education department). This is the only way at McGill to get a degree studying education and technology. Fun side note: my arts degree consists of zero arts credits.

So when I say "next I asked for an exemption and was denied" this wasn't a simple matter of meeting with my adviser. The arts adviser told me to see an education adviser, who told me to see a science adviser, who told me to see an arts adviser. I estimate I sent a dozen emails to a handful of people at this stage. I was eventually denied, since saying no is less work than saying yes. So I thought I'd make an appointment and explain my circumstances, since saying no to someone's face takes more work.

Meeting with the Oracle

In the summer the stakes got high. Some of you may know already that I'm extremely fortunate to teach technology topics in a high school during my studies. Since I want a career in education technology, this is fabulous work experience and it's easily more important than any one course I could take at McGill. Unfortunately, for my final fall semester I was left with just two choices:Teach or graduate. I had to quit my job or take an extra semester for one course.

So I met with an adviser, Grace Wong-McAllister, again. I tried hard to offer alternatives:

- Could my six extra credits in education technology replace the three diversity credits? No.

- Is there any other course I could take instead of this one diversity course in the fall? No.

- Is there a summer course I could take instead? No.

- Could I get an exemption? No.

The last point is especially fun. She asked if I had previously done relevant course work that could exempt me from this course. I answered: "well, yes. I have a BA in English literature. Maybe half my essays were about race, gender, religion, or cultural diversity." She looked at me like I was a block of mouldy cheese that just spoke to her. "No no no... that won't do."

Crossing the Threshold

"It's a long shot, though."

An inter-university cooperation group called CREPUQ might let me take an equivalent course at Concordia while I'm a McGill student. Pretty soon this became my very last option. If I couldn't take this course at Concordia, I'd have to quit my fantastic teaching job or take an extra semester for one course. I'm still baffled by the incredible stupidity of this situation. All because of a 20 minute overlap on one day.

The Trials

Luckily, I had no problems checking Concordia's schedule because I remembered my old login credentials. The course existed! And it fit in my schedule! So I filled out several pages of awkward CREPUQ web forms. My program of study was not an option so I chose a generic option instead and left a note.A day later: rejected. Invalid program of study.

Okay. I resubmitted. This time I just lied and said I was an education student.

I could see now that my request must pass through a gauntlet of administrators. The next one in line is only notified once the one above them approves my request:

- 1st program adviser - McGill

- 2nd program adviser - McGill

- Registrar - McGill

- Adviser - Concordia

- Approval of Registrar - Concordia

- Confirmation of Registrar - Concordia

Two months later, I got CREPUQ approval to register for the course! Victory..?

The Crisis

After re-activating my old Concordia account (not easy) I found that I could not enrol in any courses. I had to contact "enrolment services". They eventually removed that lock.Next, I hit a "reserve capacity is met" lock. I contacted enrolment services again. They tell me to ask the department. Okay. Calling the department took a few days of trying because their office was moving during the summer. I spoke to an administrator we'll call "Sarah". Sarah is the mountain gatekeeper from the comic. She asked for details by email, I happily sent them. Her email reply, verbatim:

"i verified but unfortunately there are only spots for Concorida students."

Okay... I asked when the leftover slots would open for independent students. I gave my story and circumstances.

"sorry but the course will not open up,it is only for Concordia students"

I see. So I previously got a BA from Concordia, I'm a re-activated "independent" Concordia student, I'm probably doing a master's at Concordia soon, but I'm not enough of a Concordia student for Sarah?

Outpost Bureaucracies

I'd like to take a moment to explain my term "outpost bureaucracy". This is where a lower employee is assigned god-like responsibility over some very obscure task in a bureaucracy. The catch is that it's so obscure that nobody cares about it. For example, approving inter-university independent student requests in one department. It's an outpost, so it's very lonely and there's no prestige. But it's an outpost! So there's nobody around to criticize any decisions. When that lone adventurer comes to the mountain summit, what is the outpost sentry tempted to do? Justify their self-importance by harshly exercising their power with impunity.

The Ordeal

So I phone someone else in the department of education. I give my best performance explaining my circumstances and try to elicit sympathy. She sounds optimistic and suggests I send her an email with all the details. Thank you! I send the email. Nothing. Two weeks later I follow up: "Hey? Any news?" No response. It's been months now, still nothing. I phoned and left a message, nothing.I called the graduate department to see if they can pull some strings for a future student. I spoke to a nice guy, but nope.

I called the Concordia CREPUQ coordinator. Also a nice guy, but nope.

Slaying the Dragon

What finally worked was a carefully crafted email. I employed several tactics:- I sent it to the Concordia registrar from my CREPUQ request instead of the advisers. I reasoned that registrars had more power because the advisers were serving as a spam filter. My first invalid request was denied by an adviser and never saw a registrar's inbox. People who are difficult to reach tend to have more power.

- I quoted Sarah verbatim, including her tragic misspelling of "Concorida".

- I mentioned that someone in the registrar's own department was not responding to phone calls.

- I wasn't whining about my situation. Instead, my main request was for CREPUQ to remove this course from their list since Concordia is obviously not cooperating.

- I said I wanted to help future students going through the system.

- Finally, I requested that only available courses be listed on CREPUQ.

That last point is vital. I was asking the registrar to get involved in a long process and do a lot of work. Nobody wants to do work. Several days later I got a phone call... from Sarah! Sarah who previously denied me entry unconditionally. She was now remarkably kind and helpful. I'm thinking... maybe someone important came to the outpost?

For the sake of completeness, this wasn't the end, just nearly. Sarah said she unlocked the course. It didn't work. I call, no answer. I get an email saying she registered me herself! I check... oops! I'm registered in the wrong course. 445 instead of 454. Chronic dyslexia! Apparently her "director" gave her the wrong course number. Maybe we've identified my saviour.

Finally, I'm now registered for the right course and everything is dandy!

Return with the Elixir

So what did we learn on this hero's journey?- When you make offerings to many gods and your life takes a positive spin, it's hard to say who helped. I think it was the registrar email but really, who knows? Like the gods, the registrar never answered.

- Emails tend to produce "no"s. Phone calls are more like long drawn out "no"s. But meet the Oracles in person and don't leave until your path is before you.

- This journey had many characters. Mentors, shadows, tricksters, heralds, and shapeshifters. I estimate this whole process directly involved fourteen administrators (I left out details). FOURTEEN. Does that seem right to you?

Alternate Ending

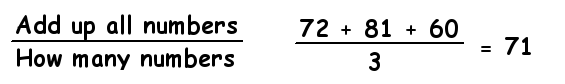

Here's how we used to do course registrations:Dear reader from 2015, does this look ridiculous to you? Well registering through CREPUQ (while it worked in the end) seems far more ridiculous to me than the picture above. Solving my scheduling problem required an estimated forty emails, one external organization, six phone calls, and three meetings in person. All spread out over five months and fourteen administrators.

So how should this have worked? How many people should have been involved in fixing my scheduling issue? How about zero.

Don't be a pessimist now! Do you think you could have told these registration administrators from the 1960s that they'd be replaced by a computer? The only difference between then and now, is they didn't have the technology we do.

Course Registrations Should be Provincial

Why the hell do different universities manage their own course registration platforms? It's like schools are paying software companies to make Microsoft Word two hundred times separately. It's like they're saying "but my documents are special because my university is special". Your university is not a special snowflake. Students register for courses in all universities in a fundamentally similar way.This could be managed centrally by the highest branch of government in charge of education: the provinces. We can pay to get it right, make it flexible, and remove no autonomy from universities. Meanwhile there could be one way to register for university courses for each province. Every university can chip in and they'd save a ton of money by eventually cutting support staff. Here's what I want to see:

- When I search for a course on McGill and it's not there, I'm shown a list of equivalent courses offered at other schools. I just click a "register" button, agree to some terms, and I'm done.

- Schools can set their own limits on how many courses can be taken externally.

- Schools choose which of their courses participate - just like now.

- Schools set their own limits on how many external students are allowed in each course.